who says: “You just want to talk politics all the time.”

There remains much discussion about when “the right time” to “talk politics” is. The conversation seems to be held from several positions: There are young people who find that the slow-moving nature of bureaucratic government is not worth the time it takes to get acquainted with the terms, ideas, and players involved in that government; there are entrenched pundits who incite that it is not the right time to talk about politics based on the current conversation’s allegiance to that speaker’s particular brand of punditry; there are liberal democrats who invoke the phrase as a way of blunting the political demand foisted on them by their constituency and the progressive wing of their party; and there are conservatives who invoke it whenever the conclusions therein clash with their solidly built and individualistic worldview.

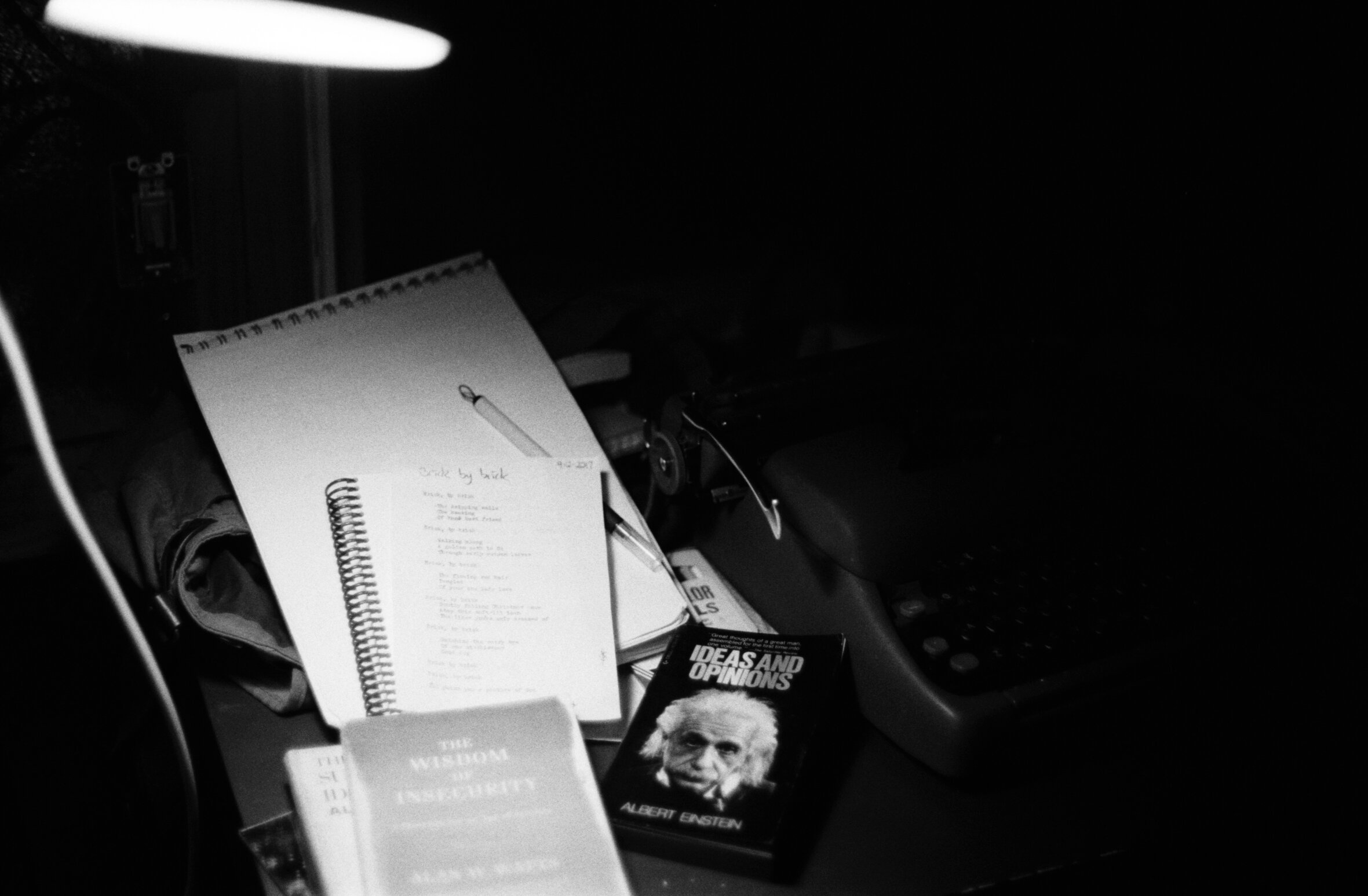

Henceforth, I address the young people’s group to which I belong but whose sentiments I do not share. I am no historian or political theorist, and so the deliberation of the larger trends I leave to the learned. More-so, I want simply to attend to the basics of involvement in the discourse:

1). American political life and her primary issue is in the lack of conversation-between, of a natural struggle of ideas, what Chantal Mouffe calls ‘agonistics’ (“The agonistic confrontation is different from the antagonistic one, not because it allows for a possible consensus but, because the opponent is not considered an enemy to be destroyed but an adversary whose existence is perceived as legitimate.” Mouffe, Chantal. “For A Left Populism”, Verso, 2019. pg. 91). At some point in the liberal hegemonic takeover, thought to be around the 1980’s with Reagan and Thatcher, but probably beginning in the late ‘60s, we entered a stage of ‘post-politics’ or ‘post-democracy’ where we thought quaintly that all the big stuff was out of the way, and now it is just the details left for experts to tidy up (Mouffe disagrees with this premise of political consensus in post-democracy, saying, “Indeed, the fundamental question is not how to arrive at a consensus reached without exclusion, because this would require the construction of a ‘we’ that would not have a corresponding ‘they’. This is impossible, because the very condition for the constitution of a ‘we’ is the demarcation of a ‘they’.” Ibid.). Since this post-democratization, we have allowed our hypothesis of ‘neutral expert caretakers’ to simmer, as the cascading crises of capitalism continually demand that we reengage in political life in a new way, beyond the gapped 4-year cycle that we currently play a part. Sometimes the errant voter under 25 will engage in the 2-year cycle if they’re really plugged in, for the congressional races and so on, but it seems uncommon, and nearly extinct for mayoral or city council elections!

2). The life of the contemporary American youth, that is to mean those born after 1993 up until voting age, dependent on the natural development of political consciousness, is bombarded by dilemma and crisis. Starting at the bottom is the ecological crisis; then, the educational and debt crisis, hard-to-find jobs, and no healthcare (barring those lucky enough to be carried over on their parents’ until age 25); further, the affordable housing crisis. If one does find themselves employed, no (or very little) protections by union or otherwise exist for job security; and as a mere garnish to these problems, no discernible political agency to change these conditions. After all, we do not live in a political or democratic world, but a post-world, one that has in itself been created by a particular brand of politics, for it is not the field or system of politics that has disenfranchised voters, but politicians espousing a particular Politic (that is, liberalism). “Experts” of economy and law are the handlers and gatekeepers to minuscule changes in policy, political programmes, and general groundskeeping of the status quo, although they quaintly elect a mouthpiece as President of the United States. After we elect who gets to tell us the bad news, we check out of the expert deliberations, as we are told to, and await the crises, natural and manmade (although with the demarcation of this epoch as distinct, being Anthropocene, it is likewise us who foment and contribute to the intensity of ‘natural’ disasters). It is certainly easy to fall into a pit of disregard toward this unmoving system, these crises, and turn to anger at our political impotence.

3). It is likewise easy to search, and find, explanations for these things in the way of conspiracy theories and the like that claim apoliticism and a New Way to Think (generally exploiting the distrust of the aforementioned expertocracy that we find ourselves in, and inciting rabid distrust for larger systems that are merely misused, not irrelevant; i.e. the media, climatology, etc.). While there may be kernels of truth to some of these theories, they are largely espoused by charlatans, stoking xenophobic and anti-semitic sentiments and conclusions already partially present in the populace. They speak on these things in ways only meant to incite rebellion against a straw-man world they themselves have built. Of course, this fruitless relationship between the politically disillusioned and the conspiracy theorists, as well as between all other venues that steal the mental bandwidth of the citizen, benefits only those groundskeepers of the status quo. Because we are disorganized politically, while tempted into making grand claims of specific conspiracies, we thus render our concerns utterly refutable. It seems then that the issue to be confronted is of our political agency, what can we actually do, or think, or believe, or fight for, that actually changes something?

4). In order to understand what fundamentally can change, we require a wider perspective, and we do that by adding one or more equalized alternatives to the first. In the case of how we operate our politics, it is by adding other methods of doing so to our discussion. Socialism and Communism have been officially banished since the inauguration of our post-world, with only fringe groups, often at great personal expense and public ostracizing, pulling the ideas through the decades to live on in our political moment today. This is no disrespect to the growing Democratic Socialists of America or the Communist Party of the USA, who would no doubt refute the belittling of their impact, and I mean not to do so here; it has been huge. Many heroes abound in our story of resistance, though given the official ejection of those ideas from the discourse, we hardly know it, and have instead learned our history only as it looks brightly on capitalism and her conquests, casting shade and distrust on all other alternatives. It is important to state simply: capitalism is only one of several political systems that we may choose as guide to our lives.

5). Indeed, not only is politics that field of office-inhabitance, some desk with a name placard in an inaccessible building; it is the field of popular organizing, or organization, just as much as it should be discursive. In fact, we overcompensate in our choosing of representatives, tending to the point of identity idolization, or more aptly pedestalization, for it is not always their personal idiosyncrasies that attract us but simply their titles and certifications as relating to “politician” and what they “seem” capable of (evidenced by incumbent candidates frequently winning due to that descriptor alone); always we consider our candidate through the lens of strict utilitarianism over humanism, values given to us through our capitalist histories. Our current highbrow and haughty politicians seem above reproach, and who would ever want to become one of them? There is little desire to participate in politics as they are, stuffy and exclusive, for many of the young voters of the country. An injection of passion and idealism has been made manifest by a successful new wave of, not only progressive policy discussion, but progressive representatives in Congress. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY), Rashida Tlaib (MI), Ilhan Omar (MN), Ayanna Pressley (MA), Katie Porter (CA), and many others are among a vanguard splitting through the political conversation with bold ideas and accountability in all the right places. As it turns out, our old conception of the politician is likewise only one of many. Where we formerly accepted in dejection the detached politician who represented unknown analysts, lobbyists, and experts, we now know our potential in the successes of these aforementioned Congresswomen, the most democratically representative politicians we can hope for at present. Indeed, the ones who can (and positively do) lay foundations for a democratically socialist future.

6). Our political landscape is in the throes of this fundamental potential for change. Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci said, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot yet be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” His historical context was greatly different than our own, and the possibility of the birth of a new social order is very much possible today; the moment of demand is even more pointedly thrust upon us by the recent coronavirus pandemic, no less than any other structural issue by which the pandemic merely laid bare. A notable and indeed morbid symptom of this moment is our current right-populist President, whose actions demand resistance, and whose message demands a left populist response (for again, as Mouffe writes: “To stop the rise of right-wing populist parties. It is necessary to design a properly political answer through a left populist movement that will federate all the democratic struggles against post-democracy. .. A left populist approach should try to provide a different vocabulary [from right populism] in order to orientate those demands towards more egalitarian objectives.” Ibid., pg. 22). That process of federation is indeed taking place, but on all fronts. In a simply unprecedented move by former President Obama, the consolidation of power behind his former running mate, and like-minded liberal, Joe Biden, took place just as Senator Sanders was showing a national winning capacity, and drawing a clear defining line for the liberal agenda as distinct from the progressive, labor, and socialist movements which, as it happens, were all bundled (or federated) by the Bernie Sanders campaign. Nevertheless, the liberal majority of the Democratic Party is locked down now, behind Joe Biden. The progressive wing is still in hearty support of Bernie Sanders’ vision for the necessary, and his Not Me, Us message of solidarity. The strongest “official” popular coalition of the progressive or socialist left would be the Democratic Socialists of America, and the crowd around them of left literature and educational resources. Besides the citizenry, there are also the congresswomen mentioned above, Sanders in the senate, a new Progressive Caucus inside the democratic party founded by some of its youngest elected members, and many more candidates besides for local and federal office.

7). Among the many other specific and morbid symptoms of our current situation, one that is most encompassing is the geological one—our newly ratified Anthropocene. Although long contested as an official epoch, the Stratigraphy Commission of the Geological Society of London, founded in 1807, never acknowledged the legitimacy of this new epoch, until a 2008 report in the Geological Society’s journal GSA Today, citing extensive earth studies findings, such as the presence of unnatural radioactive isotopes deep in the ice of our planetary poles, among much, much more. The report concludes finally that the Earth has now entered “a stratigraphic interval without close parallel” in the last several million years. (ref: Davis, Mike. “Old Gods, New Enigmas”, Verso, 2018. pg. 203; Zalasiewicz, Jan, et al.. “Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene?”, GSA Today, February 2008.) There are numerous other startling statistics regarding this Anthropocene, but the most important in whole to me is the utter novelty of experience for our species. What our world will be and feel like in the year 2100 (according to the IPCC’s modest projections), it has not been or felt like for 15 million years. The genus Homo to which we belong, meanwhile, “appeared only two and a half million years ago”, and has thus never experienced the Earth system as we now find it, and as it will become in the foreseeable future. Neither are we biologically or culturally adapted to deal with these changes, for we are among those who must do the adapting. Consequently the answers to our predicament come firmly within the jurisdiction of political action. “In the time of the Anthropocene, the entire functioning of the Earth becomes a matter of human political choices.” (Bonneuil and Fressoz. “The Shock of the Anthropocene”, Verso, 2017. pg. 24-5).

What I most hope to convince fellow voters of near age is that serious political engagement certainly makes a difference in our world; it is a matter of desire and effort to do so in the first place, and the direction of those efforts towards egalitarianism or oppression. For, “those who care not to remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” By letting the mirage of a post-political world obscure the importance of an agonistic political struggle, we are willingly abdicating our political power, leaving others who are more personally ambitious to create our world (and who belong to a demographic that will not be here when worldly catastrophe rears in earnest). We do this while insistently reducing our analysis to “politics are fucked” or some other such lazy thing. Yet it is not by voting alone that we broaden our political aspirations, or our hopes for utopia. We must first talk about the change we want to bring, and educate ourselves and one another, for no man is an island to himself. No better political candidates will appear than those among and around you, including you. Therefore, to allow ourselves to be politically unconscious is to accept a social myopia, where we are what capitalists grant us as: consumers; and we are stuck consuming only what is put before us by others.

To the derision of “talking politics all of the time,” it is appropriate to point out that involving oneself in the problems of politics is not to join some alien field of its own, but to learn how our own lives already connect to others through the ecopolitical domain. In place of environment or politics alone, there is now the Earth system as we have made it through industrialization and inhabitation of majority swathes of ice-free land (around 84% is under direct human influence; ref. The Shock of the Anthropocene, Bonneuil and Fresssoz, Verso 2017, pg.9). We must now, however, develop and live differently, as the old way has brought us to and nearly over a deep chasm’s precipice, engendering all the dangers before us. Therefore, in order to progress for all peoples and not just the privileged, old and superfluous distractions must be curtailed and substituted for action toward the egalitarian dictums of socialism, in earnest. Begun by understanding our voter power, it develops into power over personal theory and accountability, and then of pubic policy and solidarity, and then of political structure and coalition building, finally onto a new hegemonic order completely, entailing equal access to its power.

We must bring ourselves to this utopia! Or fail trying… for finally, “The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones.” And for that, we must participate! The creation and implementation of a more egalitarian system of social organization and distribution of resources depends on it, and specifically on the white-skinned population of North America and Europe, who contribute most in the world to excess materialism in general and, consequently, the carbon emissions wreaking havoc on our planet.

Vote. Organize. Educate.

In solidarity.